Industrialist Paper No. 8

The Trust Spiral

One quality escape can lock a supply chain for years

This series argues that American manufacturing already exists as a national system, but it is hard to query, hard to verify, and therefore hard to coordinate. This essay focuses on a narrow claim about what happens when that verification fails:

After a single high impact supplier failure, buyers add controls that measurably reduce awards to first time suppliers, increasing supplier concentration, introducing opacity, and raising the probability that the next disruption propagates into schedule slips. Onboarding cycle time for new suppliers increases, and quote to award rate declines for non incumbents.

The mechanism is a compounding loop, where distrust becomes policy, and policy reshapes the network. Trust, here, is not vibe or familiarity. Trust is the probability that a buyer will place a PO on a new supplier using only portable evidence.

Mechanism

A quality escape is not only a defect, it is a governance event. The buyer gets punished twice, first by scrap, rework, and field exposure, then by internal loss of credibility. The CFO sees warranty and rework. The program manager sees a ship date. The quality director sees a corrective action request. The sourcing team sees their vendor choice as the root cause, even when the real cause is a missing control point in the work package.

That internal punishment creates a predictable procurement response. New gates appear in the vendor packet. A certificate of conformance is no longer enough, now you need material traceability, heat lot linkage, calibration records, and an AS9102 first article package with forms that match the drawing revision. A receiving inspection checklist expands, the supplier questionnaire grows, and an audit becomes mandatory for jobs that used to be placed on reputation and a short phone call. This is rational inside the buyer’s incentive stack, but it is also how distrust becomes a compounding loop.

The loop closes because gates change who can even compete. The first thing that falls out is the unknown domestic shop that could have done the job, but does not have the right paper stack, or cannot afford the audit overhead, or cannot wait 90 days for onboarding. The surviving suppliers are the ones already inside the fence. Volume concentrates, schedules tighten, and the system becomes more fragile because a smaller set of nodes carries more of the load.

The economics of this are visible in the cost numbers that justify the fear. Cost of poor quality routinely lands in the double digits of operations in “thriving” companies, and can be far higher in bad cases. External failures are the most expensive because they trigger returns, warranty, field rework, and credibility loss.

Evidence for generalists

You can watch the trust spiral in any shop that has lived through a quality escape. Before the event, a buyer issues an RFQ with a PDF drawing, a STEP file, and a note block that says “finish per spec.” A supplier quotes with a couple clarifying questions, gets a PO, ships parts, and sends a basic cert. After the event, the same buyer issues the same drawing, but now the RFQ includes a supplier quality manual, a 30 page questionnaire, insurance requirements, mandatory first article inspection, process change notification rules, and a demand that the supplier use a specific format for FAIR documentation.

If you want a concrete illustration of why this happens, read incident style reports and oversight memos from safety critical industries (trust me, it makes for an exciting weekend). They repeatedly point to documentation control, training, nonconforming parts handling, and schedule pressure as contributing factors that degrade quality.

The trust spiral is not caused by malicious buyers. It is caused by incentives. When schedule pressure spikes, the procurement team stops optimizing for optionality and starts optimizing for defensibility. The buyer’s safest move is the supplier they can explain in a postmortem, because the explanation is built out of artifacts. This incentivizes defensible buying behavior over exploratory, innovative, or even cost-saving behavior. It’s understandable to want to avoid quality escapes, though the trade-off is much harder to see unless you go looking for it.

Evidence for builders

The loop is easiest to measure in work package artifacts and in RFQ logs. Look at a supplier onboarding checklist before and after the last significant escape, then count the deltas. New required fields appear and the list becomes arduous. On the shop side, the traveler grows signoff boxes, in-process inspection steps expand, and the CMM report becomes a required attachment to the ship packet even for low risk features.

There is a documented pattern in aerospace and defense quality work that “quality escapes” often originate at control points that were supposed to prevent them, especially first article inspection when it is treated as paperwork instead of verification. When first article is weak, rejected parts and escapes follow, and buyers respond by tightening the gate.

Now connect that to supplier concentration and fragility. When you narrow the approved list, you are choosing a network topology. GAO has repeatedly flagged the consolidation of supplier bases and the emergence of single source dependencies as a risk, including in defense industrial contexts where lower tier consolidation reduces competition and increases vulnerability. The academic version of the same idea is that supply relationships can amplify shocks, where small degradations in relationship functioning propagate widely through the network.

The Prime Concentration Problem

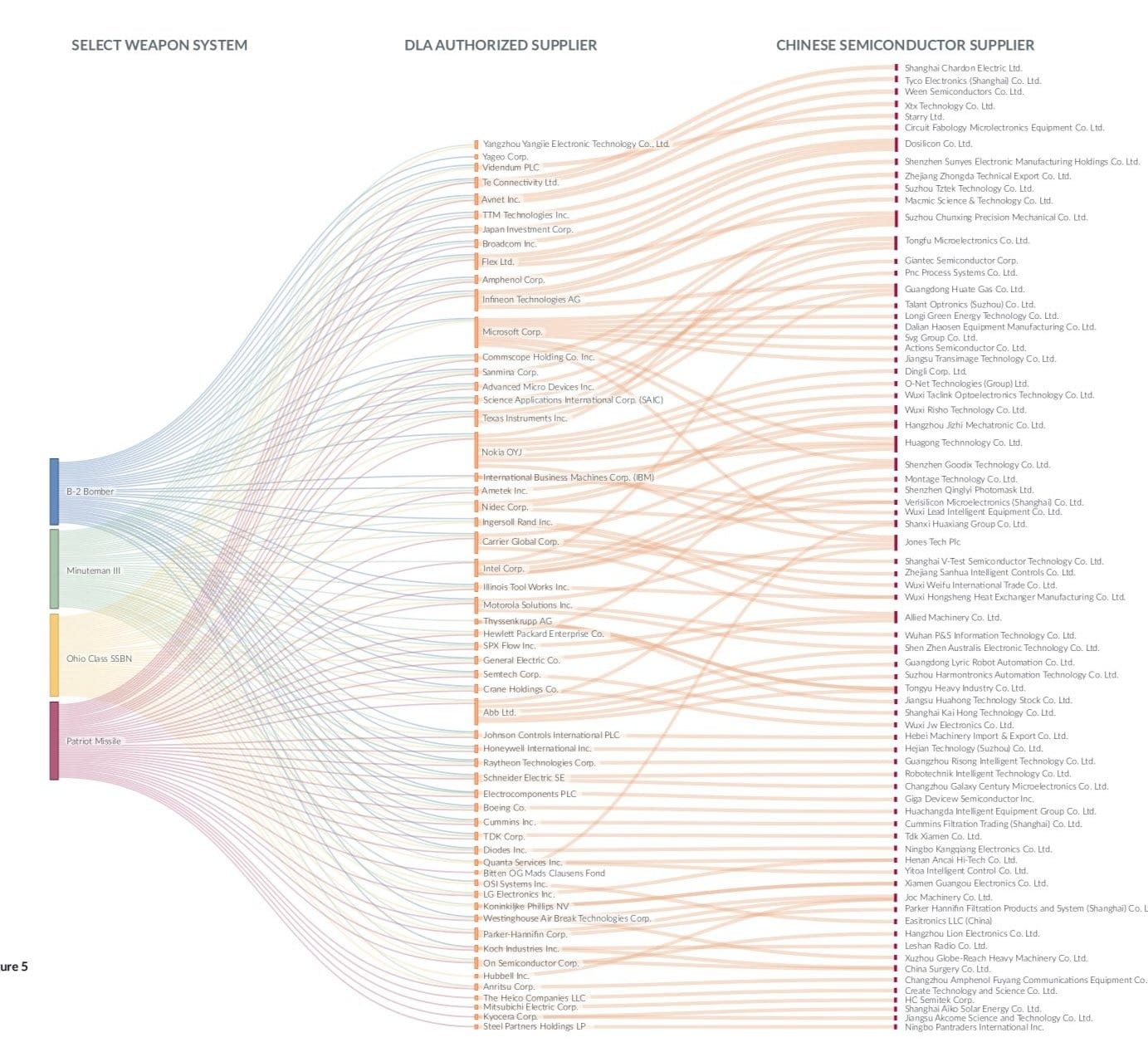

This well-circulated diagram represents one of the paradoxical outcomes of the trust spiral. Solving for “control” leads to a loss of control. Here with selected weapon systems on the left, “DLA Authorized Suppliers” in the middle, and a long tail of Chinese semiconductor suppliers on the right. In Govini’s analysis, systems like the B-2, Minuteman III, Ohio class SSBN, and Patriot show purchasing paths where an authorized channel still maps to Chinese semiconductor firms upstream. The key detail is what the Prime can prove at award time: it can point to an approved supplier record and a compliant ship packet, but it often cannot point to the sub-tier fabrication site that built the die, masked the wafer, or packaged the part. The trust artifact that exists in the Prime’s file is a name in the middle column, and the actual production chain sits one step beyond the Prime’s line of sight.

The trust spiral drives this topology. After a quality escape, the Prime narrows who it will onboard, and it shifts buys toward large, already legible suppliers because procurement can defend the decision with evidence that fits a review: approved status, audit history, and a closed corrective action on a prior NCR. That concentrates demand into Tier 1 integrators who are paid to deliver a schedule and a clean narrative, so they become the “risk sink” for the Prime’s anxiety. Under margin and ship date pressure, the integrator’s rational move is to preserve the outward paperwork while sourcing sub-tier capacity wherever it exists, because the Prime is evaluating the ship packet, not the factory floor. When the evidence boundary stops at the integrator, the control effort does not remove chaos, it pushes it downward until the substitution is invisible.

Real incidents show how clean paperwork can coexist with bad provenance. In 2024, regulators investigated titanium used in Boeing and Airbus jets after reports that falsified or incorrect documentation was used to verify authenticity, with Spirit AeroSystems acknowledging suspect material entered the supply chain via counterfeit records. The metal largely tested as the right alloy, but the documentation chain was compromised, which is the point: a parts system can pass mechanical checks and still be a governance failure because traceability is the trust mechanism. Defense electronics has a longer history of the same failure mode, where counterfeit parts from China were found in military systems and procurement responded by tightening controls that often emphasize paperwork compliance while the underlying sourcing paths stay complex and indirect. The Prime concentration problem is that these responses increase dependence on fewer intermediaries, and intermediaries are exactly where provenance can blur without immediately breaking the ship packet.

The operational consequence is perverse: the more a Prime tries to “reduce risk” by shrinking its direct supplier set, the more it increases hidden sub-tier exposure, because each surviving Tier 1 carries a deeper vendor stack inside its deliverable. The Prime sees a cert packet and an AS9102 package, but it does not see whether the upstream component was substituted, whether the traveler reflects the real process, or whether the inspection plan was written for the actual manufacturing route. That is why the diagram matters. It is a picture of trust being laundered through authorized channels, where the Prime’s controls remain locally consistent while the national supply chain reality drifts, one procurement hop at a time.

Implications

If distrust continues to compound, supplier entry becomes a paperwork problem instead of a capability problem. The nation keeps shops that could build parts out of the award path because they cannot clear the gate, even when their machines, fixtures, and metrology are adequate.

Supplier concentration rises because fewer nodes can accept the compliance overhead. As concentration rises, any disruption, quality escape, or late shipment has a larger blast radius, which increases the perceived need for even tighter controls.

Local efficiency investments - such as a new ERP - show diminishing returns when they do not change external trust. A shop spends a year tightening quote cycle time in ERP, but the RFQs arriving are still low intent and non-repeat because the shop is not discoverable to buyers outside its incumbent circle. The estimator workload moves, the award rate does not

A practical coordination layer would treat trust as an evidence object. It would bind identity to RFQs, bind revisions to drawings, bind ship packets to cert packets, and expose consequence driven history like late ship codes, NCR closure quality, and response discipline, in a format a buyer can audit without a custom onboarding project.

Outro

National self sufficiency requires more than capacity. It requires that a buyer can place a PO on a new domestic supplier with the same confidence they have in their incumbent, using evidence that is portable and hard to fake, and perhaps most importantly, evidence that is actually tied to the part and not simply the output of a team of quality control experts and auditors.

The practical failure mode is distrust. It looks like a swelling vendor packet, longer onboarding lead times, and a shrinking award funnel that concentrates work into fewer hands while increasing opacity into the actual origins of parts and materials.

Paper 9 will take the next step: it will show why trust cannot be inferred from profile pages or directories, and why verification must attach to work artifacts like RFQ completeness, revision control, inspection records, and ship packet closure codes.

Questions for you

- After your last quality escape, what new items were added to the vendor packet, and how many of them actually reduce defect escape rate versus just increase defensibility?

- What share of awards in the last 12 months went to first time suppliers, and how did that share change after the last major NCR or SCAR?

- In your RFQ log, what is the no response rate, late quote rate, and clarification count per RFQ, and which requirements correlate with fewer qualified responses?

- For a shipped job, can you reconstruct the full evidence chain from drawing revision to traveler steps to inspection plan to CMM report to cert packet, without asking a person to explain missing context?

- Which suppliers are effectively single source today, and what is the measured lead time and schedule risk premium created by that concentration?

- If you tightened gates tomorrow, which capable domestic suppliers would be excluded purely by paperwork, and what would that do to on time delivery and price over the next two quarters?