Industrialist Paper No. 7

The Hidden National Supply Chain

The supply chain exists, but it is not queryable

Ask a simple question, “How many factories are in the United States,” and you immediately hit a problem: we don’t know. Some counts treat a “factory” as any manufacturing establishment, including very small facilities with a handful of employees. Other counts emphasize large plants and ignore the long tail. Estimates are between 250,000 and almost 700,000. A single company can report one site as one establishment, or split a campus into many establishments by function and reporting convention.

Now ask the operational version of that question, “Where is the national supply chain,” and the problem gets worse. The Census Bureau’s Business Register is described as the backbone record of U.S. establishments, but establishment-level records are not available for public use because federal law protects individual business data. County Business Patterns will tell you how many establishments exist by NAICS code and geography, but it is published as summary statistics, not a list you can route an RFQ to. The closest thing most manufacturers and buyers bump into in day-to-day work is the federal contracting identity stack, SAM.gov registration, UEI, and the small-business search tools populated from it. Those systems help the government buy goods and services, but they only cover entities that choose to register to pursue federal awards, and parts of a record can be restricted from public search, so it cannot serve as a complete, routable map of the national supply chain. And don’t get me started on NAICS as the way to categorize manufacturers.

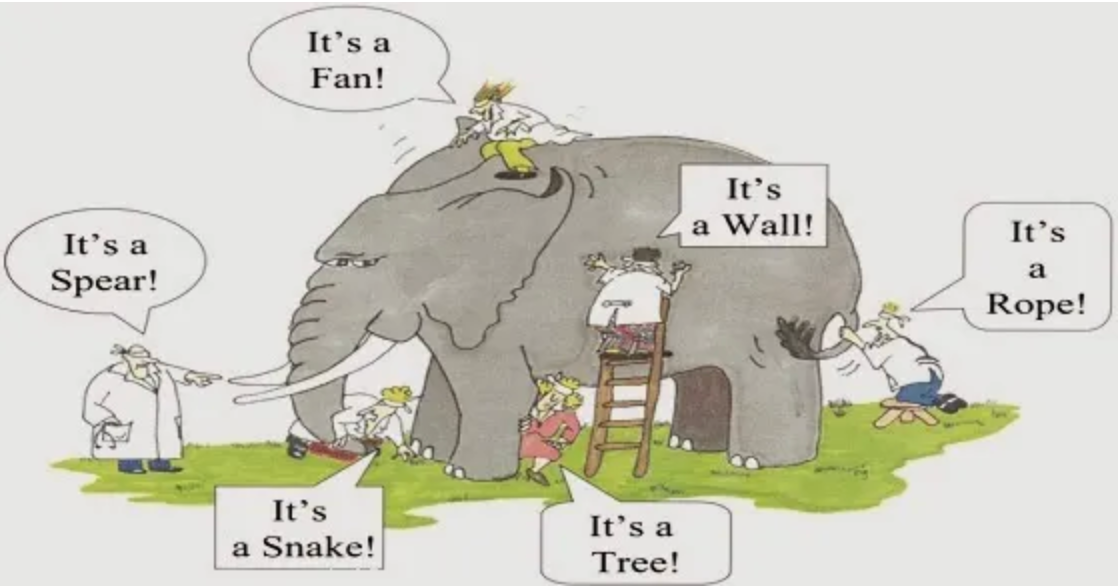

We know the United States has a real manufacturing base, but no canonical way for a buying organization to discover it and qualify it with evidence. Buyers know about different parts of it through the tools they use, the experiences they have, and the business cards that they’ve collected. But at the end of the day, it’s like the parable of the blind people trying to describe the elephant. A picture is truly worth a thousand words here:

A national supply chain is very tangible… like the elephant, it’s a thing you can see and touch and smell; VMCs running 6061, lathe cells cutting 17-4, weld fixtures clamped on tables. It’s in industrial parks and barns and garages. It is also boring paperwork. It’s the vibrant community on Manufacturing X and LinkedIn and at conferences and trade shows. The evidence exists, but much like the elephant, putting it all together for the disparate touchpoints is difficult.

Most supplier discovery and qualification and re-qualification work (i.e. “supply chain building”) in U.S. manufacturing is caused by non-portable facility identity and execution evidence, not by a lack of supplier capacity. When we talk about a “queryable” supply chain we mean “a buyer can search, filter, and route work based on verified identity, capability evidence, and performance history, not marketing fields.”

Why directories do not solve it

A directory is a list of names with marketing fields. A routable supply chain needs proof attached to work packages. A shop can list “5-axis machining” and “ISO 9001,” and the buyer still cannot tell whether the shop will hold a profile callout on the functional surface, run the right datum scheme in the probe routine, manage revision control on the traveler, and deliver a clean cert packet that survives an audit.

Even government-sponsored directories tend to be scoped to specific sectors, voluntary, and explicitly disclaimed as non-endorsements. That is not a criticism. It is a clue. A directory can help you find candidates. It cannot, by itself, carry the liability of being wrong.

Why Google does not solve it

Google finds what is optimized to be found. The best shops in a region are often the least noisy online because they are busy running travelers. Many do not want inbound RFQ blasts from unfamiliar buyers. Many have capability pages that are outdated by two machine moves and one quality manager resignation. A buyer who routes from search results is routing from copy, not from shipment evidence. The buyer then learns a predictable lesson: discovery is cheap, qualification is expensive. That lesson becomes policy.

Both Search Engines and Directories also lend heavily to the “RFQ noise floor” issue that we discussed in Paper No. 6; buyers don’t have a large enough Rolodex or they’re not getting responses so they go out and do a generic search for suppliers, find them in directories and search engines and start blasting their demand out to these imperfect matches, with no real sense of what their capabilities are. This is why we’ve seen some shops shy away from being discovered through these tools.

Why the Rolodex does not scale

A Rolodex, or a collection of business cards, a contact list… is a personal trust graph. It works until it doesn’t. It works when the part family is familiar, the material is common, and the buyer can call the owner and get a straight answer about lead time and inspection. It fails when a program changes, a cert stack changes, or a special process shows up that requires a sub-tier with traceability. Perhaps the most significant failure of this approach is on the unknown-unknowns test. Buyers may be happy with the shop they’ve been working with… but maybe there’s an even better shop around the corner that they’re totally blind to. They could be missing out on opportunities to scale, save, or continue to improve. It’s a good way to get stuck and not even know how stuck you are.

The Rolodex also dies with turnover. The company keeps buying parts. The individual relationships do not persist in a form that another buyer can route with confidence. The result is vendor development done repeatedly inside each firm, as if every firm is the first one to discover that a traveler and a cert packet are the real product.

Why trade shows feel necessary

Trade shows are the physical substitute for a missing identity layer. If you cannot verify a facility through portable evidence, you go look someone in the eye, ask what machines they run, ask what they do for inspection, and try to infer whether their cert discipline is real. This is expensive, slow, and biased toward whoever can afford booths and travel.

Trade shows also select for presentation. A buyer is trying to solve a routing problem for a drawing and a ship date. The trade show solves a marketing problem. Sometimes those overlap. Often they do not.

Tradeshows and their resulting business card collections (Rolodexes) are both paths to the personal network solution. It’s worth spending more time on these because they’re the most common ways that buyers and suppliers get and stay connected. They seem the safest, they’re classic, it’s great to meet people in person and know who you’re working with. But they don’t scale. Let’s be honest with ourselves here; in one long lifetime we’ve gone from inter-office memos and mailing letters and paying a lot of money for long-distance phone calls to short, instant messages to do business. We live in an era of speed and connectivity. Even in classic areas of machining, processes are changing rapidly. We live in an unprecedented era of change-over in supplier ownership as the boomers retire and shops change hands or close. If you are relying solely on personal networks, expanded only through in-person events to develop a supply chain you are - at best - missing out on opportunities. At worst, you will fail as your small network fails and you won’t even realize it until it’s too late.

Why verticalization is the default fantasy

When discovery and qualification are painful, leadership starts eyeing a mill. “If we buy the VMC, we control the schedule.” That can be true for some companies with deep metrology and process engineering. For most, it just moves the burden. The work package does not disappear when you verticalize. You still need an inspection plan, gauge calibration, revision control, a probe routine, outside anodize, outside heat treat, and cert packet discipline that ties all of it back to a PO. A mill without that paperwork and measurement capability is not supply chain resilience. It is a new way to generate scrap fast.

“No man is an island” although we all really really wish we could be. It’s a common fantasy. Some folks do get close to verticalization, but no one is pulling material from the ground and delivering a finished product to a customer without a high-quality supply chain. No one.

What buyers are actually (re)building

Buying organizations have to pull together three key categories of data for each of their suppliers:

First is facility identity: who exactly is the legal entity, where is the floor, which certifications apply to that address, and who is accountable when a cert packet is wrong.

Second is execution capability: not “CNC machining,” but whether this facility can run this geometry, this material, this tolerance block, and this inspection method within a stable process window.

Third is performance history: on-time delivery against ship dates, first-pass yield against inspection reports, responsiveness against question lists, and revision control discipline measured by how often the traveler and the inspection package match the PO.

Those are not opinions about suppliers, they are artifacts and rates. Hopefully companies track them internally, many do not apply much rigor to this type of tracking. Even if they wanted to, almost none can reuse this data externally because there is no shared format, no shared verification, and no shared consequence for misrepresentation.

The point

There are really two points.

One is systemic - The United States does not have a “missing supplier” problem at the national level. There are definitely categories that need work although there are a lot of categories that are incredibly strong and deep. But, much like the people looking at the elephant, this is based on partial data. The truth is, the United States has a missing map and a missing evidence layer. Some countries have a more routable picture of industrial capacity because their reporting norms and procurement systems are more centralized, and because export-driven industrial policy created stronger incentives to standardize identity and evidence.The result is redundant supplier development performed by thousands of companies in parallel, using email threads, spreadsheets, trade shows, and expensive verticalization experiments. Buyers doing the same work over and over and over.

If coordination is computation, then supplier qualification is a data problem. What cannot be represented cannot be routed. The fix is not another directory. The fix is a portable way to anchor facility identity and attach execution evidence to work packages so a buying organization can route a drawing to a traveler with a ship date, and expect the cert packet to close cleanly.

The other is behavioral - As is often the case in these papers, we end up highlighting human behavior. In Paper 1 we talked about the desire to control through yet another standard, in Paper 3 we talked about local optimizations making national failures, in Paper 5 we talked about a lack of understanding leading to ambiguity (which leads to slowness and expense), in Paper 6 we talked about urgency creating slowness by raising the noise floor. Here we are talking about another form of human behavior in the form of information hoarding; evidence stays trapped inside firms because there’s no shared verification and no safe way to share it. I don’t expect these behaviors to change; we shouldn’t expect them to change. Instead the right solution has to account for human behavior and complement it, not fight it.

Implications

- Redundant supplier development occurs in parallel inside thousands of firms.

- Discovery stays cheap, qualification stays expensive.

- Verticalization doesn’t fix it; it just shifts the supply chain burden elsewhere; it’s still necessary, just in a different form.

In our next paper, No. 8, we will talk about The Trust Spiral. Another topic that looks at system-wide issues and behavioral topics.