Industrialist Paper No. 12

From RFQ to Request

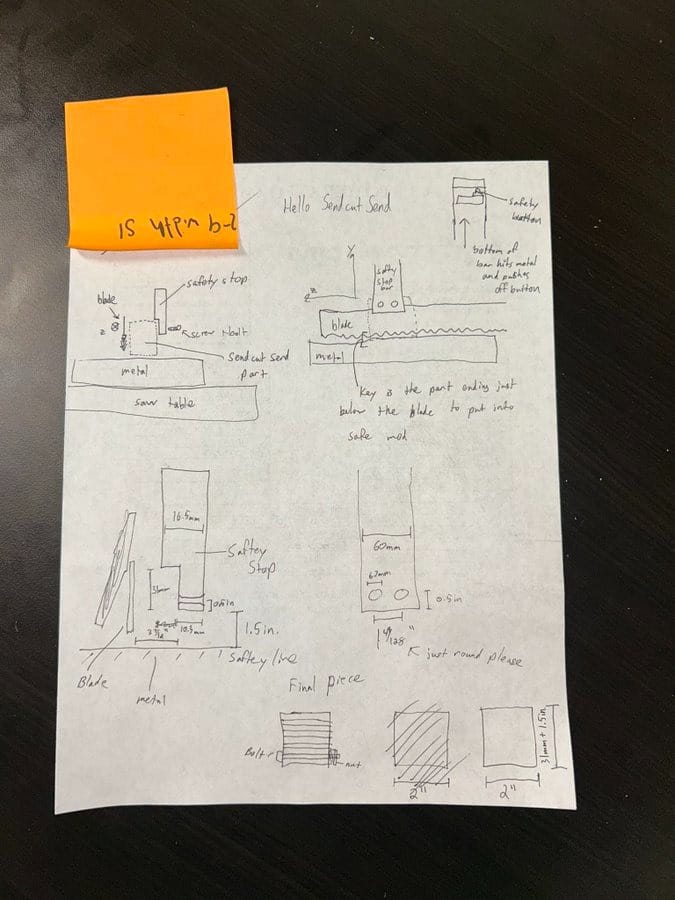

Our little story: The phone rings at the quoting desk at 3:47 p.m., and it is never a casual call. A buyer is in a bind. They need parts by Friday because a customer changed something late. They talk fast, they lead with urgency, and they leave out constraints because they do not know which ones matter. “It’s a simple bracket, just need it quick,” they say, then promise to email the drawing and model while they’re still on the line. The files arrive a minute later:

The buyer thought the call would be faster. It feels faster in the moment, but it moves the panic downstream into the quote, the traveler, the fixture plan, and receiving inspection, where missing constraints become rework instead of questions.

This series is a systems blueprint for coordinating American manufacturing without central command, by reducing the noise between buyers and shops and turning real needs into routable work. Paper 11 introduced the universal request object as the unit that can move across company boundaries without losing meaning. This paper’s claim: When inbound work is represented as a request, meaning intent plus explicit constraints plus allowed assumptions tied to a revision locked drawing and model packet, the median clarification count and revision churn per quote drop, and quote turnaround time improves for the same part complexity.

An RFQ is a document bundle, usually a PDF drawing, a STEP, and an email thread. A request is an intent with constraints: material spec, tolerance bands, critical features, lead time target, cert requirements, finish requirements, inspection expectations, shipping constraints, and the assumptions the buyer explicitly allows. The difference matters because shops do not quote documents. Shops quote risk, and risk is created by missing constraints that get filled in by improvisation.

The mechanism: constraint serialization

In truth, the phone call is a cry for help, and it’s happening all across US manufacturing every day. It is an audit trail of missing serialization, because the only place the missing constraints can be resolved is a synchronous conversation where tribal context gets reconstructed in real time. A fixed form field cannot capture what the job actually depends on when the drawing packet is messy, the model and print disagree, or the finish requirement changes the fixture plan and inspection plan. A request works because it turns the messy bundle into a checkable constraint set that can be validated, routed, and quoted with a traveler in mind.

Forms fail - even at the edges of instant quote capabilities - because they assume the world is clean. Manufacturing inputs are mixed media, PDF prints, STEP models, spec PDFs, emails, photos, and references to prior POs. The gaps are conditional, and the conditions are often not visible until someone reads the tolerance block, notices a tight positional callout, or realizes the anodize note implies masking. When the abstraction is “fill out the RFQ form,” the system pretends everything important is known at intake. The quote desk knows that is false, so it reaches for the phone.

Constraint serialization is the act of turning all that ambiguity into explicit fields and explicit defaults, tied to specific artifacts. It is not the same as making buyers type more. It is the opposite, because the system can extract candidates from the drawing notes, the GD&T frame, the material callout, and the model geometry, then require confirmation only where ambiguity changes cost, lead time, or inspection. The output is not a prettier RFQ PDF. The output is a request record that can be checked against a drawing revision, a model revision, a cert packet requirement, and an inspection expectation.

How buyers actually send work today

Most buyers do not “submit an RFQ.” They send work the way work is already moving: a forwarding email with a PDF drawing, sometimes a STEP, and a sentence about urgency. The true requirements are scattered across a PO reference, a prior NCR, a note that says “cosmetic,” and a verbal instruction about whether substitutions are allowed. The drawing packet might include a tolerance block, but the buyer expects the shop to infer which features are critical because “it’s obvious” from the assembly.

When buyers do provide structure, it is often the wrong kind. They will provide quantity and shipping address, but not inspection expectations, or they will provide a lead time target but not a must ship date tied to a build schedule. They might include “material: aluminum” without an ASTM or AMS callout and without stating whether mill certs are required. They will attach a PDF with a rev letter in the title block, but the email thread includes a redline screenshot that never made it into the controlled drawing. Every one of those gaps turns into estimator time, and estimator time is the scarce resource.

The result is a predictable pattern. The buyer thinks the drawing is the job, so the buyer sends the drawing. The shop knows the drawing is evidence, not a constraint set, so the shop either calls, sends a question list, pads the quote, or declines quietly. If the shop calls, the call resolves the job, but the resolution rarely becomes structured data attached to the RFQ record. Next time, the same buyer sends the same kind of drawing packet, and the same shop calls again. The phone becomes a coordination prosthetic, and the prosthetic prevents the system from learning.

How shops triage inbound work

The first pass at a quote desk is not pricing. It is a go/no-go decision based on whether the work package can be made coherent quickly. An estimator scans the title block for revision, then checks the tolerance block and the notes for finish, special processes, and material spec. They look for any callout that implies a specific fixture, a specific inspection plan, or a third party process like heat treat or passivation. They check quantities, then check lead time, then check whether the drawing packet includes enough to build a traveler without guessing.

This triage is an operations decision under uncertainty. If the tolerance block is missing, or the GD&T scheme implies CMM work but inspection expectations are not stated, the quote is risky. If the finish note says anodize but does not specify Type II vs Type III and does not address masking, the quote is risky. If the drawing and model disagree on a hole pattern and the precedence is not explicit, the quote is risky. Risk shows up as margin padding, lead time padding, a question email, or a phone call, because the cost of being wrong is an NCR, scrap, or a dispute at receiving with an inspection report.

Shops also triage based on the expected behavior of the buyer. If the inbound email thread suggests slow responses, frequent revision churn, or moving targets, the shop treats the RFQ as a time sink. The quote desk constraint is estimator attention, not spindle hours, so the shop allocates attention to RFQs that are likely to convert into an award and not likely to explode into a week of clarifications. This is why “more suppliers” does not automatically increase throughput. Without structured requests, adding suppliers increases outbound noise and increases inbound triage load.

The missing constraints that create rework

Most rework begins as missing constraints at intake, and it can be named precisely. Precedence and revision control is one. If the drawing says Rev C and the STEP is Rev B and nobody states which one governs, a shop will choose a path and later discover the choice was wrong when the buyer sends a new PDF or a receiving inspector rejects parts against the print. This is not a philosophical problem. It is a revision lock problem tied to a drawing filename, a model hash, and a request record.

Material specification and cert packet is another. “Stainless” is not a spec, and “6061” is not a complete spec when the cert requirement matters. If the buyer needs a mill test report, heat lot traceability, or DFARS compliant material, that is a constraint that changes supplier eligibility and lead time. When it is missing, the shop quotes a default and later gets a change request that forces a re-quote or forces the shop to eat cost. The cert packet is not paperwork overhead, it is a routing constraint.

Finish, special process, and inspection expectations are the most common hidden multipliers. A finish note that says “anodize” without specifying class, dye, sealing, cosmetic requirements, and masking might be harmless for a noncritical bracket, or it might be the entire job if critical surfaces cannot be touched and threads must be protected. Inspection expectations have the same shape. If the buyer expects a CMM report, a first article inspection report, or a specific sampling plan, the quote changes because the inspection plan changes, and the traveler changes. When those expectations are missing, the phone rings, or worse, the quote goes out based on a guess.

Lead time is often underspecified in a way that creates chaos. A buyer writes “need ASAP” or “rush,” but does not provide a must ship date tied to a build schedule, or does not state whether partial shipments are acceptable. A shop then assumes a conservative lead time, the buyer shops the quote, and nobody learns. The request object needs a lead time target and a must ship date, because those constraints allow the shop to decide whether to pull the job forward, whether to quote expedite, and whether to route the job to a subcontractor for a finish operation.

What a request looks like in implementation terms

A request is a record with three parts: an artifact set, a constraint set, and an assumption set. The artifact set contains the drawing PDF, the STEP model, and any referenced specs, plus optional evidence like a prior NCR or a photo of an assembly. The constraint set contains the fields that must be explicit to quote responsibly: precedence, revision lock, material spec, tolerancing scheme, critical features, finish, special processes, inspection expectations, cert requirements, quantities, lead time target, must ship date, and shipping constraints. The assumption set contains the defaults that are allowed when the drawing is silent, and those defaults must be acknowledged, because hidden assumptions are what create disputes.

The request also needs a state machine that reflects real quoting behavior. “Received” is not enough. You need “parsed,” then “missing constraints flagged,” then “clarification in progress,” then “ready to quote,” then “quoted,” then “awarded” or “declined.” Every transition should be tied to an artifact, a revision lock, or a closure code, because otherwise the system cannot learn which missing constraint caused the delay. This is the implementation level detail that separates a marketing form from an industrial control loop.

The phone fits into the request object, but only if it becomes structured output. A call should not vanish into memory. If the estimator calls to confirm that the anodize is Type II black with masking on threads and cosmetic class A on one face, that is not “notes.” That is a finish constraint and an assumption update tied to the drawing revision and the request ID. Capturing that turns the phone from a prosthetic into a data source, and it is the first step to making the next RFQ easier than the last.

Implications

If requests remain document bundles, the system rewards padding, silence, and cherry picking because those are rational defenses against ambiguity in the drawing packet. Buyers then experience domestic quoting as slow and expensive, even when the actual machining time is straightforward, because the quote desk spends its time reconstructing intent and acceptable assumptions. This pushes buyers toward brokers, offshore shops, or incumbent relationships, not because those options are inherently better, but because they have lower coordination latency.

If requests are serialized constraints tied to artifacts, routing becomes possible without coercion. A shop can accept work that matches its process capability and its inspection capacity because the constraint set is explicit. A buyer can compare quotes because the assumption set is explicit, and differences are visible in the quote package and the traveler plan. Over time, the system can learn which missing constraints cause clarification loops, because the closure codes, revision churn, and question count are measurable and attached to specific request fields.

This is a national weakness because manufacturing is a network of nodes, and the limiting factor is often the quality of information that moves between nodes. When coordination is weak, we keep using the phone, and the phone prevents compounding because it produces no shared structure. When coordination is strong, the phone becomes optional, used for edge cases, and the default path becomes a request object that can move across the industrial base with its meaning intact.

Outro

American manufacturing does not fail only on capacity. It fails on transmission, because intent and constraints degrade as they move from buyer to shop to subcontractor to receiving inspection. The practical failure mode is ambiguity that creates latency, and latency that kills routing. If we want domestic first without fantasy, the unit of work has to be a request that can be verified, routed, and quoted without reconstructing the job on a call.

Paper 13 follows directly. Once the request object exists, the next question is what must be present before a quote can be real. That boundary is the minimum viable work package, and it is where inference, flagging, and human clarification become a disciplined system instead of a weekly firefight.

Questions to Ask

- In your RFQ record, where is drawing vs model precedence declared, and what artifact proves the revision lock, a rev letter in the filename, a model hash, or a controlled PDF from a PDM export?

- What percentage of inbound RFQs require a synchronous phone call before the quote goes out, and do you capture the call outcome as structured updates to finish, inspection plan, cert packet, and shipping constraints?

- Which three fields most commonly trigger clarification loops at the quote desk, material spec, finish details, inspection expectations, tolerance scheme, and do you have closure codes that tie those loops to a specific missing constraint?

- How often does revision churn occur between “RFQ received” and “quote accepted,” and is the churn driven by a drawing rev change, a model change, or an assumption dispute about a critical feature?

- When a finish note is present, do you require explicit confirmation of class, masking, cosmetic requirements, and post process inspection, and is that confirmation attached to the traveler and the inspection plan?

- Do you represent lead time as both a target and a must ship date tied to a build schedule, and do you capture whether partial shipments, alternate material, or alternate finish are acceptable assumptions?